There’s no doubt that email and text messages have phased out handwritten letters in our everyday lives. However, for those who are incarcerated, physical mail can be a lifeline. In October of 2021, North Carolina’s Department of Public Safety (DPS) started to outsource mail processing services to TextBehind in an effort to combat drug trafficking in prisons. This move prevents those in prisons from receiving original copies of letters, art, cards, and photos sent from their loved ones. Instead, their letters are sent to a processing facility in Maryland where they are scanned and analyzed. Imprisoned people then receive a printed copy of their mail. This switch is a part of a trend of private companies capitalizing off of some of the United States’ most vulnerable populations.

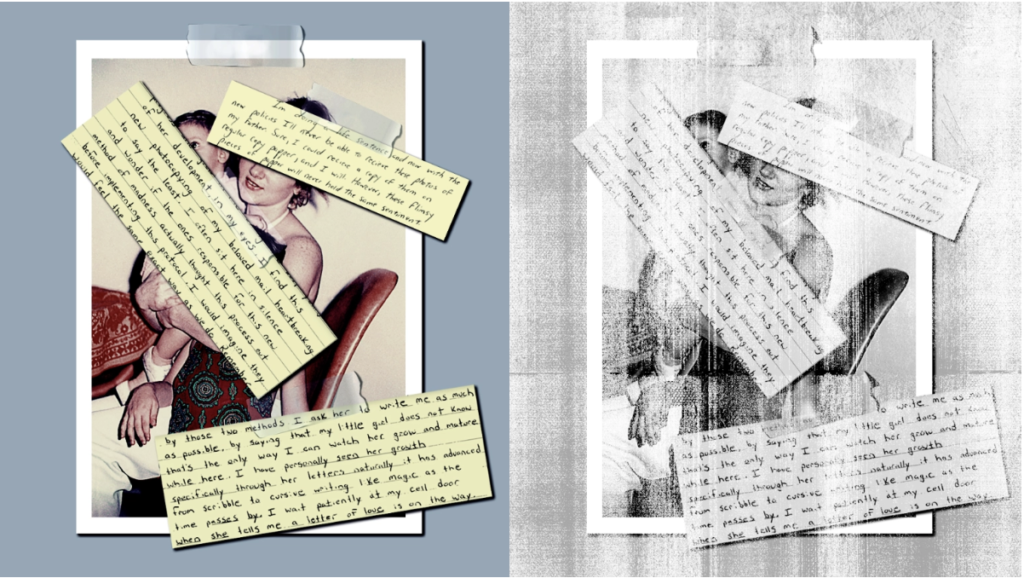

DPS boasted a 50% drop in drug possession after piloting TextBehind in its women’s prisons in 2020. TextBehind is a Maryland-based telecommunications company that digitalizes the mailing process. Their process ensures the elimination of contraband sent through the mail while allowing loved ones to stay in contact with those who are incarcerated. While DPS accomplished its goal, many women a part of this pilot were negatively affected. A resident at Benevolence Farm was incarcerated for this mail process change. She described the process as, “Horrible, slow, and frustrating!” She added, “I hated it because I was waiting on a letter from Benevolence Farm. TextBehind had things backed up for months! It was very frustrating.” Letters allow those who are incarcerated to not only keep in contact with their loved ones but also receive information from re-entry programs and resources. It takes luck and patience to obtain these opportunities; many of these programs often have long waitlists and application processes. One missed deadline can easily kickstart a vicious cycle of moving in and out of the prison system.

Besides visits, the mail is one of the most affordable ways that they can keep in contact with the outside world. Phone calls in North Carolina prisons cost 10 cents per minute plus a live operator fee of $5.49. They also have to pay processing fees — $3 when paying with a debit or credit card and $2 to receive a paper bill. An overwhelming portion of the prison population comes from low-income families and communities and, oftentimes, it is loved ones that have to foot these bills. Stationary, pens, and postage can be cheaper and more cost-effective.

TextBehind brings a new set of fees. Loved ones have two options when they want to send a letter to someone who is incarcerated: mail it to the Maryland processing facility or type their message up in the TextBehind app. If they choose to mail, they pay the cost of postage plus an additional fee if they would like to have their original copy sent back to them. Otherwise, TextBehind will shred it after 30 days. If they choose to use the app, fees start at $0.49 to send a message that is up to 5000 characters. Photos, greeting cards, and digital drawings made through the app come at an additional fee.

TextBehind also offers DPS another avenue to surveil incarcerated people and their communities. All mail processed through their facilities is stored in a digital archive for seven years. Currently, as it stands, DPS officials can access this archive without warrants or special permissions to assist them in any ongoing investigations. In an interview with The Charlotte Observer, Kristie Puckett-Williams, a manager with the ACLU of North Carolina, warns that “People have to be really careful about what they send in to loved ones so that it can’t be used against them or their loved ones or anyone else,”. While using mail as evidence isn’t new, storage of this information can implicate others or further implicate those already incarcerated.

North Carolina holds TextBehind’s largest prison contract. While the state isn’t profiting from the telecom company’s services, the partnership says a lot about how the State views criminal justice. Punishing everyone for the actions of a few is and will always be a step backward from justice.

Princess Jackson (she/they) is a Winston-Salem native studying English at North Carolina Central University. She was a writing intern at Benevolence Farm for the Spring 2022 semester.